Castlegregory and Vicinity in the Mid-Nineteenth Century

Source:- www.nyuirish.net

by Ted Smyth, Glucksman Ireland House, New York University.

© Ted Smyth, 2018. All rights reserved.

An account entry in New York’s Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank (EISB) in 1853 opens a window on a remarkable exodus from the Dingle Peninsula in Co. Kerry during the period of the Great Famine. Unlike the assisted emigration from the Lansdowne estate centered further south around Kenmare, a group from Castlegregory and vicinity demonstrates how chain migration was behind their movement out of Ireland and settlement in New York. Research into 366 Emigrant Savings Bank account holders living in the 18th Ward during the period 1850-1860 reveals that of 35 born in Co. Kerry, 22 of them emigrated from this specific rural area, mostly settling in the Gas House district, where some of the men found arduous work as gas stokers.

An account entry in New York’s Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank (EISB) in 1853 opens a window on a remarkable exodus from the Dingle Peninsula in Co. Kerry during the period of the Great Famine. Unlike the assisted emigration from the Lansdowne estate centered further south around Kenmare, a group from Castlegregory and vicinity demonstrates how chain migration was behind their movement out of Ireland and settlement in New York. Research into 366 Emigrant Savings Bank account holders living in the 18th Ward during the period 1850-1860 reveals that of 35 born in Co. Kerry, 22 of them emigrated from this specific rural area, mostly settling in the Gas House district, where some of the men found arduous work as gas stokers.

Bridget O’Brien, a native of Castlegregory, opened EISB Acct. No. 3712 on February 9, 1853. The childless widow of Maurice O’Brien, she ran a Porter House on 21ststreet between First and Second Avenues. She reported that she landed in New York from Cork on the ship, Croma, in May 1848. There are no records of a ship called Croma in the transatlantic shipping archives, but there is record of a brig called the Cremona, which arrived in New York from the port of Cobh on July 24, 1848. The Cremona’s manifest supplied by its Master, William Davy, reveals that amongst the 55 passengers was a Bridget Callaghan, aged 24, who we can assume is the future Bridget O’Brien, as the Bank’s accountant recorded Bridget’s deceased parents as Thomas Callaghan and Bridget Foran.[1]

The Castlegregory that Bridget Callaghan left forever in 1848 had been wracked by famine and disease for two years, with no prospect of relief. It is not clear if Bridget and her siblings and cousins regarded emigration as deorai/banishment or as opportunity for better times, in contrast with abject poverty and misery at home.[2]In many ways it was both banishment and opportunity. Bridget joined two brothers and three sisters who had already emigrated to New York: Michael, Jeremiah, Catherine and Judy; another sister, Norry, lived in Massachusetts. This left only one sister in Ireland, Mary,[3] who emigrated to New York in 1854, married Thomas Spillane, and settled at 194 East 22nd Street, around the corner from her sister.

What was life like in Castlegregory, a remote village on the north shore of the Dingle peninsula, before the devastation of the Famine? Lying in the parish of Killiney and the barony of Corkaguiney, Castlegregory derives its name from the tower house built by Gregory Hussey, whose descendant, Walter Hussey was defeated by Cromwellian forces in 1641.[4]In the 1830s, the town erected a large Roman Catholic church, whose pastor, Fr. Fitzgerald, bequeathed 30 pounds per annum to educate local poor children.[5]The area was predominantly agricultural, with some fishing in Tralee Bay, and densely populated with extensive sub-division of property among children, leading to over 80 percent of the population living in huts or one-room mud cabins.[6] The principal landlord was Lord Ventry, who controlled approximately 100,000 acres, “although by the 1840s his estates were under the receivership of the Courts of Chancery and operated as the Ventry Trust property.”[7]

The end of the Napoleonic Wars lowered agricultural prices in Ireland after 1814; landlords pressured tenants for higher rents and sought to free up land for more profitable cattle grazing, so that, “by 1841, approximately 80 percent of Ireland’s arable land was under grass.”[8] The tenant farmers in turn exploited the laborers, raising the rent on their meager conacre if they improved the land, or evicted them.[9] Making matters worse, in poor areas like on the Dingle Peninsula, between 1821 and 1841 the population rose by more than 30 percent, “pressing ominously on the land’s ability to support so many inhabitants.”[10] In 1827, seeking to ease the social and political pressure, the British government repealed all restrictions on emigration and “over 20,000 Irish responded to lower fares, prosperity overseas, and deep agricultural and industrial depression at home by flocking to the New World.”[11] In 1836, the local.”[13]

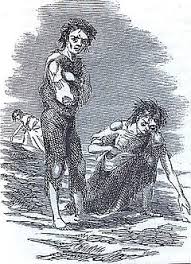

The Great Famine contributed to one million deaths in Ireland from starvation and disease, with two million people fleeing overseas.[14] In September 1846, the Castlegregory constabulary reported that the produce of the potato crop was 90 percent less than in former years and that all the laborers in the area were unemployed.[15] The Medical Officer of Castlegregory, Dr. John William Busteed, appealed for help for the people of his village on 23 February, 1847, describing the deaths from starvation and related diseases: “Michael Forhan of Tullig died on last Saturday evening from want of food. John and Denis Cronin of Keelballylahiffee, father and son, the only support of seven in family, are now in fever, the consequence is, that no one of that family has tasted food for two days.”[16]

Two Quakers, Edmund Richards and Edward Fitt, provided additional contemporary accounts in 1847 on the appalling conditions Thomas and Bridget Callaghan, and their six children—including the future Bridget O’Brien—would have endured even in the early years of the Great Famine.

At Castlegregory the state of the people is indeed distressing, we had a meeting with three of the Committee, R.F. Swindell, Parish Curate, Jn O’Kane Parish Priest, & W. Busteed M.D. Fever and dysentery prevail to an alarming extent, more than 120 cases labouring under those diseases were attended to at the Dispensary yesterday (6th day). & many that could not be attended to were sent away for the next day of attendance, of which number many may perish from inability to attend. This place is an extremely distressed locality. Death has been here in a fearful degree, reduced the population. In the Glens where no kindly hand was near to administer to the poor cottiers wants, he was left to perish with his family in his lonely cabin, and instances were told us from good authority, that the dead were found in a decomposed state.

We heard many cases of extreme misery and death and although many have suffered to an almost incredible extent, the poor creatures appear to have been quite patient under their awful visitation. Their supply of food and funds being entirely exhausted, it appearing that an immediate supply was wanted, and many starving persons in the hamlet, we purchased ½ ton meal at Bunnow Mill, 4 miles distant from present relief, and gave an order on Dingle for one Ton Rice & Two of India meal, as we found any would perish ere the government measures would take effect. This district with Clahane and Kilquhane claims the sympathy of the benevolent. Isolated far away on the shores of the Atlantic, no direct intercourse anywhere it appears these are only fishing villages. There are many persons who when able earned a livelihood by fishing, and with their patch of potatoe (sic) land managed to struggle through at ordinary seasons, and now when the failure of this chief maintenance occurred, their hopes fled, many a family has passed away to be seen here no more.[17]

The only alternative for many was emigration. Emigrants from Co. Kerry and the province of Munster departed from Cobh in Co. Cork or via Liverpool, which was the largest transatlantic port in the nineteenth century. To reach Cobh, Bridget Callaghan would have traveled 100 miles via Tralee, Killarney and Macroom, a journey then of approximately two to three days, as few could afford the mail coach to Cobh. Most emigrants from Co. Kerry to North America sailed via Cobh or Liverpool, but many also sailed from Blennerville, the port for the town of Tralee, 15 miles from Castlegregory.[18] In 1851, for example, a total of 8,732 people emigrated from County Kerry to different parts of the world, with 31 percent of them sailing direct from Blennerville for Canada or the United States.[19] Ships sailing from Blennerville lobbied Co. Kerry relief boards such as the one in Dingle to send their “paupers to the land of employment and independence” with them. Instead of “spending, it may be, two or three nights on the road (to Cork), they leave the workhouses in the morning, and in a couple of hours it may be, but certainly within the day, they are comfortably arranged in their several berths, without trouble or hardship.”[20]

The only alternative for many was emigration. Emigrants from Co. Kerry and the province of Munster departed from Cobh in Co. Cork or via Liverpool, which was the largest transatlantic port in the nineteenth century. To reach Cobh, Bridget Callaghan would have traveled 100 miles via Tralee, Killarney and Macroom, a journey then of approximately two to three days, as few could afford the mail coach to Cobh. Most emigrants from Co. Kerry to North America sailed via Cobh or Liverpool, but many also sailed from Blennerville, the port for the town of Tralee, 15 miles from Castlegregory.[18] In 1851, for example, a total of 8,732 people emigrated from County Kerry to different parts of the world, with 31 percent of them sailing direct from Blennerville for Canada or the United States.[19] Ships sailing from Blennerville lobbied Co. Kerry relief boards such as the one in Dingle to send their “paupers to the land of employment and independence” with them. Instead of “spending, it may be, two or three nights on the road (to Cork), they leave the workhouses in the morning, and in a couple of hours it may be, but certainly within the day, they are comfortably arranged in their several berths, without trouble or hardship.”[20]

An additional benefit was quick access to the Atlantic, reducing the crossing by at least a day. The Kerry Evening Post on March 19, 1853 referred to the pending departure of the ship, Lady Russell, with nearly 400 passengers en route to New York, noting that “the greater proportion of their passage money has been provided by remittances from America. Indeed, in some cases, for money that was received only by Monday’s mail, emigrants will be on their way to America by Friday evening.”[21] The family members and neighbors from Castlegregory gravitated to the 18th Ward in New York, many of them living in the same tenement houses or shanty dwellings and working in the gas lighting industry, which operated a major utility on the block between East 21stStreet and East 22nd Street bounded by First Avenue and Avenue A.

Many emigrants from Co. Kerry also departed for North American ports on the Jeanie Johnston, a three-masted barque built in Quebec and bought by John Donovan of Tralee in 1847. The ship made her maiden voyage in April 1848 from Blennerville harbor to Quebec with 193 passengers on board.[22] Over the next seven years the ship made 16 voyages to North America carrying over 2,500 emigrants, bringing a cargo of timber from America to European ports on the return journey. No lives were lost on the voyages, an achievement attributed to the ship’s master, James Attridge and the ship’s doctor, Dr. Richard Blennerhassett.[23]Among these passengers was James Moriarty from Anascaul, who married Mary Spillane from “over the hill” in Castlegregory and settled at 118 East 22nd Street, not far from Bridget O’Brien.[24]

Bridget’s first cousins, Eugene and Jeremiah Forhan (EISB Acct. No. 2901) left Castlegregory via Blennerville in 1852, following the path of their two sisters, Mary and Catherine, who were by then settled in Syracuse, New York. Among the other neighbors, relatives and friends from the district were Ann O’Connor. She left Castlegregory in 1849, her future husband, Jeremiah Kane of Clydane having landed in New York in 1846. They opened EISB Acct. No. 24441 in July 1860, at which point her mother was in Nova Scotia and her father was dead. Michael Mulane (EISB Acct. No. 2657) from the Stradbally area, one mile from Castlegregory, sailed from Liverpool to New York in the winter of 1849 to join his brother John. A year following Bridget Callaghan O’Brien’s departure, Sylvester Egan left Castlegregory via Tralee on the ship, Triumph (EISB Acct. No. 2658). Michael O’Connor who left the village in 1853 on the Rajah from Tralee, opened EISB Acct. No. 1091 in February 1856, the record noting he was now married to Johanna Spillane.[25] John Griffin emigrated from Killiney in 1851 (EISB Acct. No. 8787). In 1852, another neighbor from Castlegregory, Morgan O’Connell (EISB Acct. No. 4112), had sailed on the New Brunswick from Tralee to join two brothers in New York, another having emigrated to Sydney, Australia. The year 1854 marked the high point of emigration from Blennerville to North America, with 3,003 departing that year, but thousands would continue to leave from that port through the 1860s.[26]

[1] Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild (ISTG), Brig Cremona, http://immigrantships.net/v8/1800v8/cremona18480724.html, and ancestrylibrary.com.

[2] Kerby A. Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 240-241

[3] EISB Acct. No. 3712, New York Emigrant Savings Bank, AncestryLibrary.com.

[4] Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, 1837, http://www.libraryireland.com/topog/

[5] Ibid.

[6] Shane Lehane, The Great Famine in Kerry (Tralee: Independent Publishing Network, 2015), 21-24.

[7] Ibid., 2.

[8] Miller, Emigrants and Exiles, 214.

[9] Lehane, The Great Famine in Kerry, 28-30

[10] Miller, Emigrants and Exiles, 219

[11] Ibid., 197.

[12] Quoted in Martin Lynch, The Land and People of Maharees and Castlegregory: A History 1560-1960 (By the author, 2016), 20

[13] Ibid., 221

[14] In 1841, the population of Kerry was 295,000, but had fallen to 160,000 by 1911. Remote rural communities like Castlegregory were particularly affected. In 1837, 970 people lived in 160 houses in the village, “mostly thatched”, whereas by 2011, the census recorded only 243 inhabitants, a quarter what it was before the Famine, Source: Population Classified by Area, Central Statistics Office (Ireland). April, 2012, 40.

[15] Lynch, The Land and People of Maharees and Castlegregory, 22.

[16] Ibid., 26.

[17] “Report of Friends, April 1847”, The Great Famine in Kerry 1847, research by Kay Caball, My Kerry Ancestors, http://mykerryancestors.com/great-famine-kerry-1847/

[18] Liam Kelly, Geraldine Lucid and Maria O’Sullivan, Blennerville: Gateway to Tralee’s Past (Tralee Training & Employment Authority Community Response Programme, c1989),134.

[19] Ibid., 134.

[20] Ibid., 146.

[21] Ibid., 169.

[22] “History of the Jeanie Johnston”, http://jeaniejohnston.ie/history/

[23] Ibid.

[24] EISB Acct. No. 11195, New York Emigrant Savings Bank, AncestryLibrary.com.

[25] It is quite likely that she was related to Mary Spillane Moriarty.

[26] Liam Kelly, Geraldine Lucid and Maria O’Sullivan, Blennerville: Gateway to Tralee’s Past, 134.